In recent days, the University of Minnesota’s Mapping Prejudice Project has taken on renewed importance, as it provides a foundation for understanding the history of racism in the Twin Cities and its social and economic effects.

The project has uncovered, documented, and mapped the systematic use of property deeds to enforce racial segregation in the Minneapolis area. U of M Libraries Mapping Prejudice project director Kirsten Delegard, along with co-founders Kevin Ehrman-Solberg, Ryan Mattke, and Penny Petersen, set out to develop an interactive map designed to help the public visualize the spread of racial covenants through different Minneapolis neighborhoods over time.

Mapping Prejudice taps into a growing community interest to confront painful legacies of racism. In the wake of the death of George Floyd, now more than ever the public is seeking answers to work towards a more equitable future. The project has been cited in numerous news stories in recent days, including articles in Time magazine, the Washington Post, Quartz, and other publications.

“Minneapolis has some of the highest racial disparities in the country”, says Delegard of the project’s origins. “I was interested in looking at the past to understand how we got to that place.”

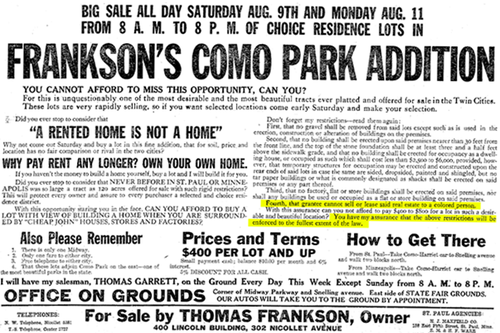

When Delegard began searching for evidence of racial disparities in Minneapolis history, she found a set of documents in the Hennepin County property records that had created a system of racial segregation starting in the early 20th century. These documents were housing deeds that included racial covenants—a clause that restricted the sale of certain houses and lots based on a person’s race.

Although racial covenants have been illegal since the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the racist language remains present in many housing deeds today. Covenants also weren’t unique to Minneapolis, says Delegard. They were used in every American and Canadian community.

Delegard says that those practices enshrined inequality in the law, creating unequal opportunities that have had repercussions lasting well beyond the period when covenants were enforced. For decades, black citizens in Minneapolis were systematically denied equal rights to homeownership—one of the most important ways to build wealth in America.

The project found that Minneapolis was not particularly segregated before 1910. After that, a big shift towards segregated neighborhoods abruptly occurred as a result of racial covenants.

To this day, Minneapolis and St. Paul have among the lowest homeownership rates for black households in the nation, and the areas that were covered by covenants in the mid-century are still the whitest and most affluent parts of the cities.

The Mapping Prejudice Project won its first legislative victory this spring when Gov. Tim Walz signed a new law that allows Minnesota homeowners to amend their property deeds to renounce racist language.

As a work of public history, the map is not the end point. It’s a stop along the way—an interactive learning tool that has the power to spark an ongoing community conversation and change policy.

Watch a video about the project.

Learn more about the origins of the Mapping Prejudice Project as well as recent developments.

- Categories:

- Arts and Humanities