Losses of soil carbon under climate warming might equal U.S. carbon emissions, further accelerating climate warming

A new global analysis finds that warming temperatures will trigger the release of trillions of kilograms of carbon from the planet’s soils into its atmosphere, driven largely by the losses of soil carbon in the world’s colder places. The increase in the atmospheric CO2 concentration will accelerate the pace of climate change.

For decades, scientists have speculated that rising global temperatures might reduce the ability of soils to store carbon, potentially releasing huge amounts of carbon into the atmosphere and triggering runaway climate change. Yet dozens of studies at single locations in different places around the world have produced mixed signals on whether this storage capacity will actually decrease—or even increase—as the planet warms.

A new study published in the journal Nature, based on 49 climate change experiments worldwide, including six in Minnesota, suggests that scientists might have been looking in the wrong places.

The study, led by College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resources Sciences (CFANS) Department of Forest Resources Adjunct Professor T.W. Crowther, found that warming will drive the loss of at least 55 trillion kilograms of carbon from the soil by mid-century, adding an additional 17 percent on top of the projected emissions due to human-related activities during that period. That would be roughly the equivalent of adding to the planet another industrialized country the size of the United States and thus have a big impact by accelerating climate change

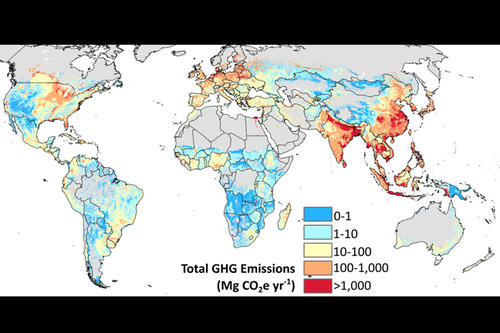

Critically, the researchers, including CFANS Dept. of Forest Resources Regents Professor and Institute on the Environment Fellow Peter Reich, found that carbon losses will be greatest in the world’s colder places, at high latitudes, which had largely been missing from most previous research. In those regions, massive stocks of carbon have built up over thousands of years and slow microbial activity has kept them relatively secure.

Most of the previous research had been conducted in the world’s temperate regions, where there were smaller carbon stocks to begin with. Studies that focused only on these regions would have missed the vast proportion of potential soil carbon losses, said Crowther, who conducted his research while a postdoctoral fellow at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies and at the Netherlands Institute of Ecology.

“Carbon stores are greatest in places like the Arctic and the sub-Arctic, where the soil is cold and often frozen. In those conditions microbes are less active and so carbon has been allowed to build up over many centuries,” said Crowther.

“But as you start to warm, the activities of those microbes increases, and that’s when the losses start to happen,” he said. “The scary thing is, these cold regions are the places that are expected to warm the most under climate change.”

The results are based on an analysis of data on stored soil carbon from dozens of climate warming experiments conducted over the past 20 years by more than 30 co-authors in different regions of the world.

The study predicts that for one degree of warming, about 30 petagrams of soil carbon will be released into the atmosphere.

“This is a big deal,” Reich said, “because the Earth is likely to have warmed by 2 degrees Celsius by mid-century, releasing as much carbon over that time period as will be emitted from fossil fuel burning in the United States.” A petagram is equal to 1,000,000,000,000 kilograms.

The study considered only soil carbon losses in response to warming. There are several other biological processes—such as faster plant growth as a result of carbon dioxide increases or slower plant growth due to climate warming and drought—that could dampen or enhance the effect of this soil carbon feedback. Several long-term experiments in Minnesota forests and grasslands led by Reich are addressing these questions.

“Getting a handle on these kinds of feedbacks globally is essential if we’re going to make meaningful projections about future climate conditions,” said Crowther. “Only then can we generate realistic greenhouse gas emission targets that are effective at limiting climate change.”

- Categories:

- Agriculture and Environment