Coping with the Mental Health Crisis

The last 13 months have brought layer upon layer of challenges and stress to college students everywhere, no less at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. As some of the heaviness lifts, the U of M is looking forward with a systemwide initiative designed to stem the tide and vastly improve student mental health.

The last 13 months have brought layer upon layer of challenges and stress to college students everywhere, no less at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. As some of the heaviness lifts, the U of M is looking forward with a systemwide initiative designed to stem the tide and vastly improve student mental health.

The collective mental health of college students all across the land had already been trending downward entering the spring of 2020. Trending or spiraling, take your pick.

According to the most recent data from the College Student Health Survey, unmanaged stress was reported by 41.5 percent of University of Minnesota students, up dramatically from the 2010 rate of 26.8 percent. And 42.2 percent of Twin Cities campus students reported being diagnosed with at least one mental health condition within their lifetime.

Then came the imperfect storm of 2020: the global COVID-19 pandemic, the upheaval and movement for racial justice following George Floyd’s death in May, and the intensely contentious election season, which did not end on November 3. And just this past month, the police killing of Daunte Wright in the midst of the trial for former police officer Derek Chauvin, convicted of murdering Floyd.

Two and a half semesters into the pandemic, many students are still struggling, and it will take some time to assess the long-term effects on student mental health. But the U of M is marshaling its resources and resolve to respond, and in February University of Minnesota President Joan Gabel announced the President’s Initiative for Student Mental Health, which she hopes will help the U of M become a leader in providing mental health care to students.

It’s been kind of a sustained trauma at different levels for different people for a long, long time. And that’s the part where I think public health experts are worried about the mental health pandemic to follow.—Matt Hanson

“It’s been tough in so many ways.”

“Oh my gosh, it’s been quite a year.”

“COVID has really affected my mental health, and it has done so in expected ways.”

Those are a sampling of top-of-mind thoughts on college life in 2020-21. Students mention profound loneliness and lack of social support in almost the same breath as lack of privacy in their living situations. They’ve worried about personal and family health, food and housing, and the job prospects that may or may not await them.

And a lot of stress was brought on by a new world of predominantly online learning. With few courses offered in person in 2020-21, students holed up in dorm rooms, off-campus apartments, and with their families trying to adapt.

For Alex Rich, a senior neuroscience major and a health promotions student assistant for Boynton Health, that has led to a lack of connection, both in the classroom and beyond. “Sensing a relationship with your professor is hard over video. They feel like a box on the screen that you’ve never met,” Rich says. “How do I conceptualize where I’m at in the class and feel confident in reaching out for help and connecting with others? I think in a virtual environment that’s just really, really difficult.”

Connecting in courses is one thing. But the dearth of opportunities to connect with peers and friends socially—that mainstay of college life—has also dealt a devastating blow.

“It’s been very eerie on campus. I’ve gone only a few times because I have purely virtual classes this semester,” Rich says. “I went for a walk the other day on campus on a Tuesday at noon, which is when usually it’s chaos. But it was utterly silent.”

“How do I conceptualize where I’m at in class and feel confident in reaching out for help in connecting with others? I think in a virtual environment that’s just really, really difficult.”

—Alex Rich

She talks about how challenging that’s been for everyone, but especially first-year students, who have not yet been able to immerse in a normal collegiate life. “There is a huge divide in experience between the folks that were here on campus before all this happened and the first-year students. My heart goes out to them.”

By most estimates mental health has suffered, for students and so many others in our community. While the demand for counseling services should seemingly be at a peak, there’s actually been a drop for new-patient intakes at Boynton Health on the Twin Cities campus, says Matt Hanson, a psychologist and interim director of the mental health clinic there. But Hanson notes that there are far fewer people near campus to stop by the clinic in person, and there are limitations on how much care can be provided across state lines for students back home. “I don’t think that reflects a drop in mental health need,” Hanson says.

Boynton has continued to offer walk-in services for people in crisis throughout the pandemic, and has been able to expand the number and duration of appointments for patients.

“Being among students every day I know that the need is there more than it was before the pandemic,” says Rich. But “trying to kick-start a therapeutic relationship over video is very difficult.”

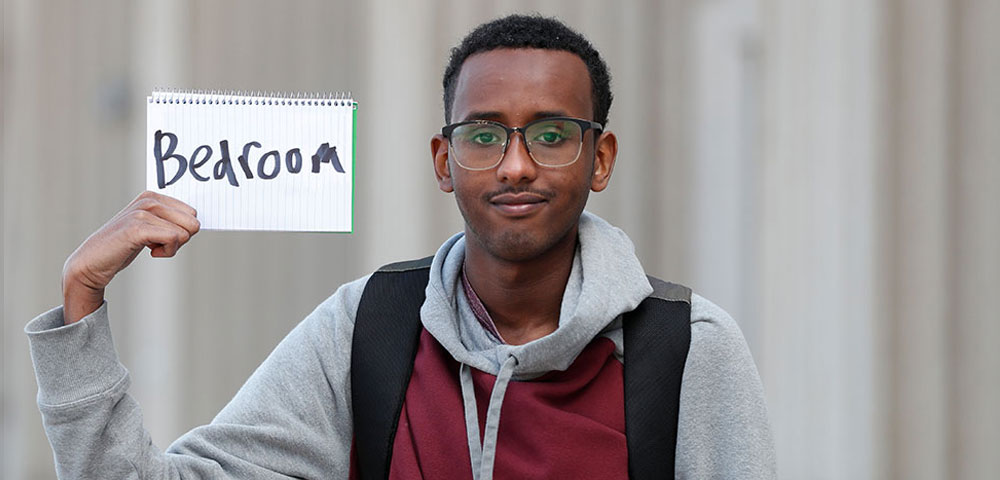

Then there’s the matter of sharing what’s bothering you—perhaps about your roommates or family members—when you’re living with them. “It’s not conducive to online therapy and talking about sensitive topics with somebody in your space,” notes Rich. “In terms of living with other people and having roommates, that’s a huge part of it for our population in general.”

- Categories:

- Health