Sentinels in the sky

The Raptor Center at the University of Minnesota is a cherished resource for research, rehabilitation, and education.

Birds have long captivated the human imagination.

They are symbols of nations, their likenesses often found on currency or adorning the tops of flagpoles and government buildings. Sports teams have been named after them, and aircraft too—the most aggressive of which often take the name of the type of bird that sits at the top of the food chain.

These are raptors—a Latin word that literally means to seize or capture, which they have evolved to do with unrivaled efficiency, using sharply hooked beaks and talons that can tear prey apart in seconds. They are eagles, hawks, ospreys, falcons, owls, kestrels, and more—commonly thought of as birds of prey.

On the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus in Saint Paul sits a center unique to the Midwest and renowned around the nation and world—The Raptor Center (TRC), housed within the College of Veterinary Medicine.

A peregrine falcon, one of TRC’s many educational birds.

Once endangered, the peregrine falcon was removed from the endangered species list in 1999.

Here, veterinarians treat sick and injured raptors with the goal of returning these magnificent birds to the wild. Some of those whose injuries are severe enough that they won't survive such a return become educational birds at permitted educational facilities like TRC—ambassadors of its many outreach programs. Tens of thousands of children (and adults) learn and interact with these creatures every year, often taking away seeds of inspiration that may someday germinate into something as magnificent as the raptors themselves.

There are only a handful of raptor centers around the country, and even fewer centered within universities. This unique relationship allows TRC to not only treat and rehabilitate raptors but also train future veterinarians and conduct research that provides insight into environmental and ecosystem health.

“We are one of the few with this integration of rehabilitation, environmental education outreach, and research,” says TRC director Julia Ponder.

All things interconnected

Scientists here often refer to raptors as sentinels—seers of environmental cues that let us know when something is wrong.

“Raptors, like humans, are at the top of the food chain—the top predators,” says Ponder.

“And the top species often reflect what’s happening under them. So they bio-accumulate contaminants, they show the impacts of habitat loss,” she says.

Dana Franzen-Klein, a TRC veterinarian who received a master’s degree from the U of M in 2019, says that part of the center’s mission is supporting ecosystem health.

“All animal species in an ecosystem are linked. For example, if a pesticide is getting into the water, that could result in fewer water insects. This could result in decreased survival of insect-eating birds. Some hawk species primarily eat these smaller birds, so within that local ecosystem there would be a decreased food supply for the hawks,” she says.

The idea that health is the intersection of humans, the environment, and animals—both wildlife and domestic—has recently begun to be called One Health, says Ponder. Yet it’s an approach TRC has taken since its founding 40 years ago.

“And today, with 70 percent of emerging diseases coming out of wildlife, that intersection—all of this—is suddenly becoming a huge area of focus,” says Ponder. “There is recognition that this is integral to all of our health. In a time of COVID, need we say anything more?”

Franzen-Klein agrees. “Different species have different niches. Turkey vultures and eagles to an extent are scavengers—they play a role in keeping the environment clean and controlling disease. Raptors also control populations of other animals. Hawks and great horned owls control rodent populations so rodents stay in balance and don’t overeat vegetation, and if they overeat vegetation that affects insect life. Raptors keep everything in balance.”

Franzen-Klein recently led a team of researchers, in partnership with Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, exploring neonicotinoids—a type of insecticide in news headlines around the world for its effects on bees. Almost all agricultural seeds are treated with some type of neonicotinoid. Franzen-Klein studied the effects a neonicotinoid called imidacloprid could have on chickens as a model for wild grain-eating birds, such as grouse and pheasants.

The research was able to pinpoint how much of the substance a bird would need to ingest to exhibit clinical signs, as well as the intensity of those signs as dosages increased.

“Even with a small number of seeds in one sitting, in as little as five minutes they wouldn’t be able to walk, weren’t aware of their environment, and in severe cases they were in a coma. We don’t know yet if the sensitivity (among raptors) is the same, but like DDT, it could have other effects,” she says.

In the late 1950s and ’60s, bald eagles and other birds began to crash when DDT thinned their eggs, killing their embryos and leading many species, including bald eagles, to be listed as endangered.

Researchers at TRC have also conducted testing on commonly used rodenticides, studied lead poisoning of eagles, and mapped what eagles can hear in hopes that an auditory tool might be developed to deter eagles from approaching wind turbines.

Listen to four different owl calls

Ambassadors of the environment

Meet Spruce, an educational ambassador

Spruce is a northern saw-whet owl—the smallest owl in Minnesota, averaging just 2.8 ounces and 6.7–8.7 inches in height. Spruce was found in 2018 on the side of the road along the north shore of Lake Superior with permanent eye damage, possibly caused by a car collision. Meet more TRC ambassadorsOther raptors of North America

“Conservation through education—that’s our educational mission,” says Mike Billington, TRC’s education program manager. And he is passionate about his work.

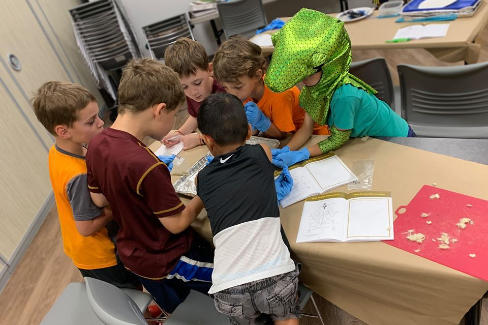

“We bring these captivating, engaging, and inspiring animals into classrooms to give kids an up-close experience with wildlife that hopefully they won’t forget. It plants a seed for when they get older. A plant can’t germinate into a beautiful thing if there wasn’t a seed to begin with,” says Billington.

In fact, TRC’s education efforts reach more than 100,000 people per year—many of them preschool, elementary, and middle school children—through virtual programs and past onsite visits and more than 1,000 programs at schools and camps throughout Minnesota and the Midwest. More than 50 of TRC’s 300 volunteers* work within its education department. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, TRC staff have developed a number of new virtual programs to help teachers meet the demands of distance learning

“We take messages the clinic learns and bring them to the public. So lead poisoning, impacts of rodenticides and neonicotinoids—we learn about these issues through our researchers’ work and the birds coming into the clinic. Our job is to communicate what we've learned so that people can think about things they can do to help raptors and the environment,” he says.

It’s no wonder Billington believes in the power of raptors. He recalls that in 11th grade, his science teacher took his class out bird banding.

“To see them up close, their wings and feather structure, and the colors. I was just blown away. They put them up against our ear so we could feel how warm they are—we could hear their heartbeat. In that moment I had this realization that I actually didn’t know what a bird was. And that was the spark. And it planted a question: ‘What else about the natural world am I missing because I just don’t know how to look?’”

“To see them up close, their wings and feather structure, and the colors. I was just blown away. They put them up against our ear so we could feel how warm they are—we could hear their heartbeat. In that moment I had this realization that I actually didn’t know what a bird was. And that was the spark."

Billington’s goal is to share that sense of wonder with others.

“We want kids to know, to feel, that the environment is something they can be inspired by. And the kids, as soon as they know we are coming, you just see them bouncing with excitement. They just can’t wait to see these birds,” he says.

Ponder agrees.

“[Raptors] really are sentinels for what’s happening out there, but they’re also tools for communication, for telling stories, for inspiring changes in people’s perceptions and behavior,” she says.

School children learn about raptors during an educational program.

Mike Billington at TRC’s fall 2019 raptor release event.

Return to the wild

In mid-August, TRC admitted a young osprey that had fledged from its nest and landed on a chute used to dispense gravel, where it tumbled down under a pile of small rocks. Workers at the gravel pit noticed almost immediately, quickly dug out the osprey, and called the center for help. After some treatment and a few weeks of exercise, the bird was released back into the wild.

TRC is full of these kinds of stories—the kindness of strangers for creatures that would rather avoid humans altogether. Some stories, like this one, end happily, while others may not.

Students come from all over the world to do advanced clinical training with TRC.

“It’s a very competitive position,” says Ponder.

2020 clinic statistics

Top 5 species

- Great horned owl

- Bald eagle

- Red-tailed hawk

- Barred owl

- Cooper's hawk

On an afternoon in late August, interns Ria Landreth and Laura Molinet are treating a great horned owl with a rib fracture. Molinet wants to specialize as a wildlife veterinarian. TRC is a perfect fit.

“Minnesota has a great reputation for wildlife. This was my top choice, so I was very happy to get here,” she says.

Molinet is a Partners for Wildlife initiative intern who splits her time between TRC and the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center to get a broader wildlife rehabilitation experience.

Landreth is interested in working with wildlife, especially big cats and other mammals, but she’ll take carnivores like raptors any day of the week.

“I’m one of those people who wanted to do this ever since I was a kid. Every summer my parents would take me to a big cat refuge in Arkansas, and that and a love of science and medicine led me here,” she says.

The raptors at the clinic can be in rehab anywhere from a few days to more than a year before they can be returned to the wild.

One of TRC’s biggest and most popular events is its biannual raptor release, where birds that have been fully rehabilitated are released back into the wild. The event often draws crowds of hundreds of people and is popular with families.

“I think of it as our opportunity to give back to the community,” says Ponder. “You see these young children with their eyes the size of saucers, because they’re like, ‘Wow.’ It’s an opportunity to change a child’s life.”

But for many of the clinic staff, it’s all about the birds.

“It is so rewarding to be able to take an animal that comes in, fix it back up, have it retain its wild nature, and then get to be re-released back into the population. It doesn’t happen with all of them, but it really is amazing, especially when you get a bird that you’ve worked on for months,” says Molinet.

And while raptors don’t say thank you, they do show their appreciation in other ways.

“The thank you,” says TRC veterinary technician Corryn Vitek, “is when it comes back with a band on its leg after 20 years of successfully living in the wild.”

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/twin-cities.umn.edu/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/AlFaHs5WFIw.jpg?itok=JAtDLek-","video_url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AlFaHs5WFIw?rel=0","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":0},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

The impact of COVID-19

COVID-19 has had a significant impact on The Raptor Center’s operations, including the temporary suspension of its critical volunteer program, which consists of more than 300 people. TRC is funded primarily through a mix of philanthropy (60%) and educational program revenue (30%). Consider giving to The Raptor Center.

Meet the people behind the story

Julia Ponder, DVM, MPH

Executive Director, The Raptor Center

Mike Billington

Education Program Manager, The Raptor Center

Dana Franzen-Klein

Staff Veterinarian, The Raptor Center

Corryn Vitek

Senior Veterinary Technician, The Raptor Center

- Categories:

- Agriculture and Environment