Jessica Deere: Wilderness Water Watch

Deep in the forest primeval of northern Minnesota, placid lakes sparkle in the sun amidst a sea of trees. But even here, the long tentacles of modern civilization have tainted the wilderness.

Deep in the forest primeval of northern Minnesota, placid lakes sparkle in the sun amidst a sea of trees. But even here, the long tentacles of modern civilization have tainted the wilderness.

“We found chemicals in an environment we thought was pristine. We tested for 158 different chemicals and detected 117.”

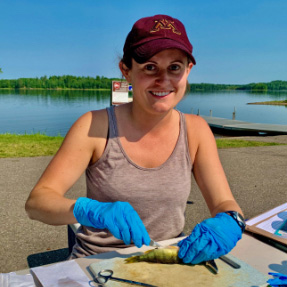

That’s Jessica Deere, a summer 2021 PhD graduate of the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) describing her study of chemicals in sediment, water, and fish in 28 northern Minnesota locations. Deere’s study area extended from Lake Superior to the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Reservation in the state’s Arrowhead region.

The chemicals detected include pharmaceuticals like antibiotics, anti-depressants, cancer drugs, and hormones, plus personal care products, DEET from insect repellent and BPA from plastics. These are among the many CECs—contaminants of emerging concern—turning up in lakes and fish around the world.

The study established baseline values against which future water and fish health can be evaluated. Both are closely connected to human health, the third branch of the One Health paradigm.

Throughout the project, Deere and her team supported what the tribe wanted and needed, focusing on how they subsist on fish, a resource of deep cultural importance. Among her colleagues was Seth Moore, the Grand Portage tribal biologist, who, though not a tribal member, is director of biology and environment for the Band.

“This was about food safety, security and sovereignty,” Deere says.

Fish tell the tale

Deere’s study lakes fell into three categories: undeveloped, developed, and wastewater effluent-impacted, where treatment water is released into the lakes. But water treatment doesn’t always target CECs, she says. Besides testing for chemicals, she examined lake trout and cisco in Lake Superior and yellow perch and walleye in inland lakes.

Her findings were eye-opening.

“The issue with CECs, and why we started focusing on these contaminants, is … we would assume these lakes receiving treated water would have high levels of contaminants because all of the pharmaceuticals that come out of people’s bodies are flushed down the drain, or people flush pharmaceuticals down the toilet, and it gets in wastewater and they end up in the environment,” she says. “But we found contaminants in all three categories [of sites], and the fish health in undeveloped sites was as poor, or sometimes poorer, as it was in the developed or wastewater-impacted sites.”

More work is needed to understand specific effects of contaminants—“What does it mean that we detected them?” she says—and whether there are population-level impacts.

“But now,” says Deere, “we have a baseline understanding as to what’s out there and what we’re dealing with.”

While the researchers learned much about how the contaminants are distributed across the study sites, “we can’t causally link fish health to the observed CEC exposure,” Deere says. “But we were able to place the contaminant results into context by what we call ‘assessing indicators’ of fish health.”

To assess fish health, the team examined fishes’ whole body health status, performed microscopic exams of fish organs, and consulted an EPA database on the effects of different chemicals.

“Because we have these data and we know these chemicals were in our fish, we know these effects could be happening in our fish,” she explains. “And we can relate that information to what we saw in the [whole body and microscopic pathology exams].”

For example, the researchers found liver cancer in one yellow perch. This result can be linked to whatever CECs the fish also had; however, with just one example, no causation can yet be inferred.

A broad slice of science—and life

The lakes Deere studied all lie within the Grand Portage Reservation and the 1854 Ceded Territory, where the Ojibwe (Chippewa) culture centers on subsistence hunting and fishing.

“The Ojibwe way of life is intrinsically linked to the waters in which these chemicals are found, but we are all responsible for putting them there,” Deere notes. “Activities further away may lead to these chemicals being in these ecosystems without a specific point source.”

Deere has always cared about “the bigger picture importance of the work I do.” In this project, she learned about treaty rights and cultural connections to fish and water.

With graduate school done, Deere is heading to Tanzania’s Gombe National Park. She and her two CVM faculty advisers—Tiffany Wolf, a wildlife epidemiologist; and Dominic Travis, an ecosystem health scientist and lead of the college’s Global One Health Initiative—have previously worked at Gombe, home of Jane Goodall’s chimpanzee studies and the long-running Gombe Ecosystem Health Project, which Travis and team began in 2004. Deere will begin at least a year as project manager in Gombe for creating One Health Hub, a new community-led ecosystem health platform. Her postdoctoral work there is partially funded through the U of M Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility Scholars Program.