Beating the blue-green blues

U of M Duluth research is on course to prevent blue-green algae blooms in Lake Superior.

It’s impossible to imagine Minnesota’s prime vacation paradise without a shimmering expanse of blue water stretching as far as the eye can see.

Lake Superior “is the number one reason people come to Duluth,” says Bob Sterner, director of the Large Lakes Observatory (LLO) at the University of Minnesota Duluth, quoting an industry survey. He has made it his mission to use his deep knowledge of the factors leading to unsightly, off-putting blooms of blue-green algae to keep the Great Lakes’ most lustrous jewel in its current state of awe-inspiring, pristine health and beauty.

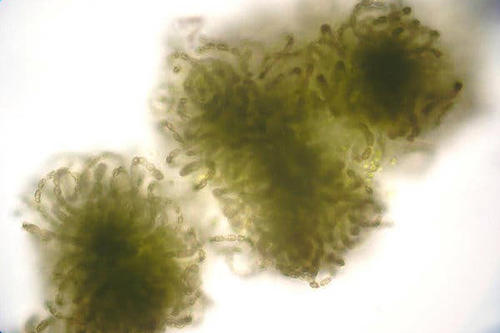

Known for its cold, clear water, Lake Superior was once considered immune to the pea-soup summertime blooms of blue-green algae (which biologists now usually call Cyanobacteria). But in 2012 one burst out along its southern shore, and in 2018 it happened again.

Preventing blooms like these—which elsewhere have been known to produce toxins that can be detrimental to human or pet health—requires a knowledge of what causes them. To date, only LLO scientists, working with colleagues at the National Park Service, have generated the data for Lake Superior that is needed to build such knowledge.

Land-lake connection

"Our businesses depend on the health of the Lake Superior watershed. For those of us in the over 17,000-job, $800 million annual tourist and outdoor industries of Northeast Minnesota, the water draws our customers."Downstream Business Coalition

Sterner and his graduate student Kaitlin Reinl have collected data on conditions in Superior and also inland lakes, ponds, and rivers that drain into it and could have contributed to the blooms. They noted that both blooms followed historically heavy rainstorms—by about 30 and 50 days, respectively. The researchers also know that for blooms to occur in the lake, four conditions must be met: proper nutrients; warm water; winds and currents that sweep algae into shallow near-shore water, where they accumulate; and a source of algae.

In lab experiments, Reinl found that the first three conditions weren’t sufficient. Blooms would not grow in Lake Superior water under optimal conditions—but they did in samples from inland waters.

“In the future, our economy won’t be based just on exploitation as it was in the past … it’s going to have to be based on a collaboration between us and nature. … We have some smart scientists at LLO and they are lighting the way.”Carla Blumberg, owner, At Sara's Table, a popular Duluth restaurant

“This indicated that inland locations provide a source of ‘seeds’—that is, blue-green cells that can reproduce and grow in the lake,” she says. ”We’ve been looking inward to the land for clues to which sites, or types of sites, are most likely to contribute viable seeds.”

She and Sterner searched for common threads between physical and chemical conditions in inland water sources and the ability of water samples to produce blue-green blooms in the lab.

The results are encouraging.

“We have tentatively identified some conditions that make a site more likely to contribute to blooms down the road than others,” Reinl says. "Also, in warm years with large storms, conditions are probably better for blue-green growth because of warmer water and higher inputs of nutrients from storm activity.”

Warm weather blue(-green)s

Data collected by other LLO scientists have revealed that Superior is one of the fastest-warming lakes on Earth—a statistic that bodes trouble for its ability to fend off future blue-green blooms.

"The way the Large Lakes Observatory is taking care of the lake is an investment in tourism, and the tourism industry in Duluth is the biggest improvement opportunity for our economic stability and growth."Ken Buehler, executive director, North Shore Scenic Railroad

As Superior warms, it becomes more important than ever to identify not only contributing biological factors, but geological, physical, and chemical conditions that set the stage for blooms. That information is coming in as LLO researchers sample rivers that feed into Superior, as well as near-shore areas of the lake. They’ve also installed subsurface sensors to monitor lake conditions.

With this data, as well as discoveries from work like Reinl and Sterner’s, LLO scientists are supplying the bedrock knowledge that will underpin efforts to control blue-greens and keep northern tourism healthy. And save a lot of families’ vacations.

- Categories:

- Agriculture and Environment

Meet the people behind the story

Robert Sterner

Director, Large Lakes Observatory, U of M Duluth

Kaitlin Reinl

Graduate student, U of M Duluth