The value of creativity reaches way beyond the fun factor. Recent work at the U of M suggests that creativity-based activities may help adolescents experiencing depression.

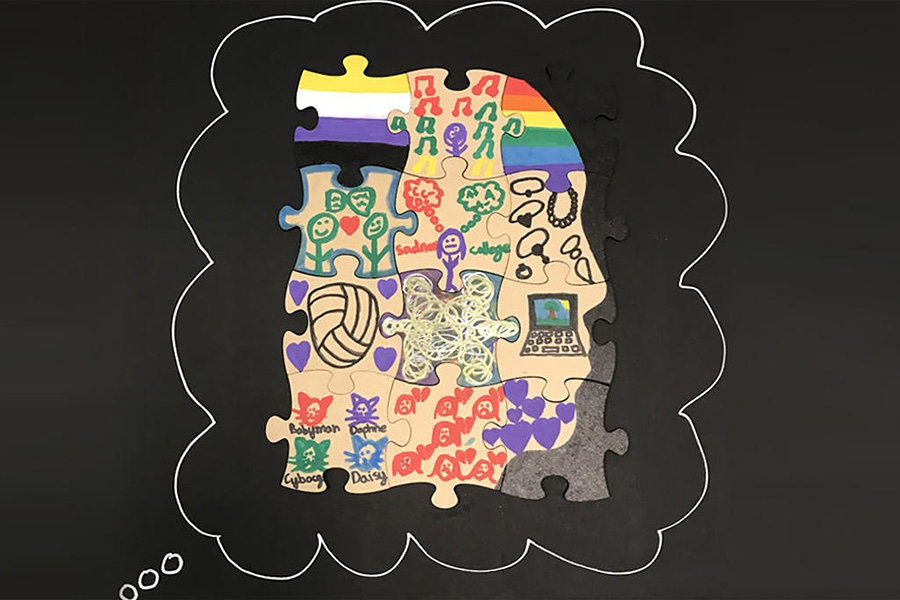

Last summer, a group of 12- to 17-year-olds—all with symptoms of depression—got together for an innovative Creativity Camp at the U of M’s Masonic Institute for the Developing Brain. There they learned how to contra dance, work with clay, write letters to the Mississippi River, make self-portraits with personalized puzzle pieces, and hike through woods to gather materials to make a communal forest.

The camp gave researchers a chance to study how young brains respond to creative activities and whether those activities can affect depression. With the National Institute of Mental Health reporting that in 2020, 12 percent—2.9 million—of U.S. adolescents in their age group had at least one major depressive episode with severe impairment in the previous year, the stakes could scarcely be higher.

“When they experience depression, adolescents get stuck in a rut with their thinking and emotions. They have a hard time shifting out of that,” says camp co-creator Kathryn Cullen, associate professor and head of the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the Medical School.Cullen notes that young people who don’t respond to conventional treatments for depression tend to lose hope. “They need something to inspire them,” she says.

Getting creative about creativity

The Creativity Camp participants had brain MRI scans before and after camp. The scans measured, for example, brain structure and brain function during both rest and a novel “imagination task.”

The early results were promising: After camp, depression symptoms were lower and scores on measures of well-being higher. And the kids all got to take home a 3-D scan of their brains.

But more than just the effects of creative activities seemed to be at play.

“It became clear that having the right setting and social environment really was important,” Cullen says. For instance, one young person told her the camp was a place where she didn’t feel alone.

“She knew she was part of a group of kids who were struggling with their mental health and that she wasn’t going to be judged,” Cullen says.

This year, the researchers’ work went global. In January Cullen and colleague Yuko Taniguchi, an assistant professor for medicine and the arts at the U of M Rochester, held a similar program at Akita International University in Japan. The researchers also plan to recruit 40 U of M undergrads for Imagination Studio, a six-week workshop involving participatory arts, self-inquiry and connection.

- Categories:

- Health

- Health conditions

- Medical

- Research